This blog post has been a long time coming, and it’s still only likely to be a waif of a thing after all that, but here goes any way.

Back in June, I gave a presentation at CELT entitled “beyond the walled garden – the story of how one learner used social media for professional learning and development” (that learner being me, of course). The aim was to make concepts regarding change within Higher Education real by bringing something of the lived experience to the discussion. As such, I related the story of how I discovered social tools for professional networking and development and how I subsequently went on to discover open education, take advantage of the new ways of learning online and to develop as a digitally literate and networked learner/practitioner. Whilst reflecting on and narrating this experience, I acknowledged a number of new ways in which the web facilitates learning and a number of new learning theories pertinent to the digital age, that is to say, learning in communities, social networks and in MOOCs giving reference to connectivism, rhizomatic learning, heutagogy and CoPs. Thinking back over it all, I found the concept of rhizomatic learning to really resonate with me, and to intrigue me equally as well. As such, rhizomatic learning is a topic that I want to understand more deeply, and to understand why it accords so greatly. Well, I’ve made a start.

I’d come across the term, or terms, “rhizome” and “rhizomatic learning” some time ago but what it signified didn’t really interest me, until I discovered, back in January, through quadblogging in #edcmooc, that the metaphor for a rhizomatic learner is the nomad. Thank you Ary Aranguiz. Now, the mention of the word nomad certainly had me interested; why, hadn’t I already got my summer vacation booked to Mongolia and China, part of which, …I kid you not, includes a home-stay with nomadic families (the adventure starts next week, by the way). The choice of destination, Mongolia in particular, seems like a natural choice to me as I generally spend my vacations roaming around and sleeping under canvas. I like to walk long distance paths and I love camping, especially wild camping. Besides, I’m a hopeless idealist who dreams of freedom and travel. Spanning time and space, I’ve read heaps of travel books and accounts from various explorers: ‘Into the Wild’; ‘South’; ‘Touching the Void’; ‘As I Walked Out One Mid-summer’s Afternoon’; ”Ghost Riders – Travels with American Nomads’; ‘In the Empire of Genghis Khan’; ‘Red Dust’… the list goes on.

The nomad in me.

Any way, enough of that. Why should it be that the metaphor for a rhizomatic learner is that of the nomad? Dave Cormier, originator of Rhizomatic Learning Theory, explains the thinking.

The nomad is trying to do what I call ‘learning’. Not the recalling of facts, the knowing of things or the complying with given objectives, but getting beyond those things. Learning for the nomad is the point where the steps in a process go away.

Hence, the learning nomad can be thought of as ‘being the thing itself’. It’s like the difference between playing a succession of notes, one after the other, and playing music, or it’s like parallel parking, if you prefer, if you think of the steps and perform them one at a time, invariably you mount the pavement. Either way, there’ s a point where you stop thinking of facts or steps and understand the act.

To me, and to probably a lot of others, a nomad more easily conjures up images of wandering across open spaces. So far though, this aspect has not come through in my reading. However, the notion of freedom and transcending boundaries seems to fit nicely with the idea of play as a habit of learning that I was thinking about in my last blog post, play as exploration that is.

Gwen Gordon, in asking “What is Play?” says that “freedom is a hallmark of play” as it softens boundaries and allows individuals to become adaptive and spontaneous. She continues, playfulness is “the freedom of the total self to move as a whole in relationship to the total environment”( p.8). Now that sounds like a nomad. What’s more, through such play, with its interactions across boundaries and it’s impulse towards both freedom and connection, transformations are made possible.

According to Dave Cormier, nomads (or those with a disposition for play as exploration) “have the ability to learn rhizomatically, to ‘self-reproduce’, to grow and change ideas as they explore new contexts”. So, what does “to learn rhizomatically” actually mean? And, where does the term come from? Well, rhizome refers to a way in which certain plants spread. Often understood as a creeping root stalks, rhizomes go out horizontally and interact with their environment. Certainly, they’re messy, disorderly and difficult to control, but at the same time they’re resilient and have a lot of important qualities, which allows them to adapt within their ecosystem. As such, rhizomes have come to represent a model for learning for uncertainty and, like the learning process of life itself, they’ve no beginning or end either.

By the way, if you have an hour to spare, I heartily recommend that you listen to the Introduction to Rhizomatic Learning that Dave Cormier did on the topic in the #etmooc archive. It’s class.

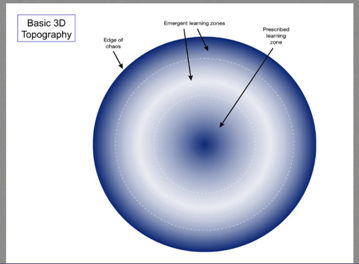

If you think about it, uncertainty is always part of the learning process. How do we know what things you’re going to need in the future; what problems you’re going to have to solve? Thus, learning, now more than ever, ought to help prepare people for, and be comfortable with, uncertainty; help them to adapt to new situations and help them to make the best decisions they can when the answer is unknown. Therefore, for a learning nomad to develop it’s no good having prescribed learning outcome as this thwarts the ability to explore, make connections, be creative and to solve problems. Besides, the point at which any new idea takes shape, and what it means, will be different for each and every learning nomad.

“Nomads make decisions for themselves. They gather what they need for their own path”.

Incidentally, a nomadic nature is something that Harold Jarche equates with the new “knowledge artisans” of the network era. Connected and knowledgeable individuals with their own learning networks and their own ways of working, individuals who are often more independent and more contractual or shorter-term than previous information age employees, all-in-all, probably more comfortable with uncertainty. Well, I can certainly live with that.

This all sounds wonderful, learning and living nirvana probably, but so far I’ve only thought of rhizomatic learning from my own point of view as a learner and not from the point of view of a facilitator of learning, so now the question becomes how can I, and other educators, help learners to develop their learning nomad abilities and be comfortable dealing with uncertainty? To defuse those predetermined outcomes, rhizomatic learning theory proposes that community becomes the curriculum… and I propose that I save that for another blog post.

Sources:

Cormier, Dave (2011) Workers, soldiers or nomads – what does the Gates Foundation want from our education system? Available at: http://davecormier.com/edblog/2011/10/22/workers-soldiers-or-nomads-%E2%80%93-what-does-the-gates-foundation-want-from-our-education-system/

Cormier, Dave (2011) Rhizomatic Learning – Why we teach? Available at: http://davecormier.com/edblog/2011/11/05/rhizomatic-learning-why-learn/

Gordon, Gwen (2007) What is Play? In Search of a Universal Definition. Available at: http://www.gwengordonplay.com/pdf/what_is_play.pdf